Portrait of Jasper Morrison by Elena Mahugo © Jasper Morrison Ltd.

“Some Designers have a complete Vision of the Future”

Interview with Jasper Morrison by Gerrit Terstiege

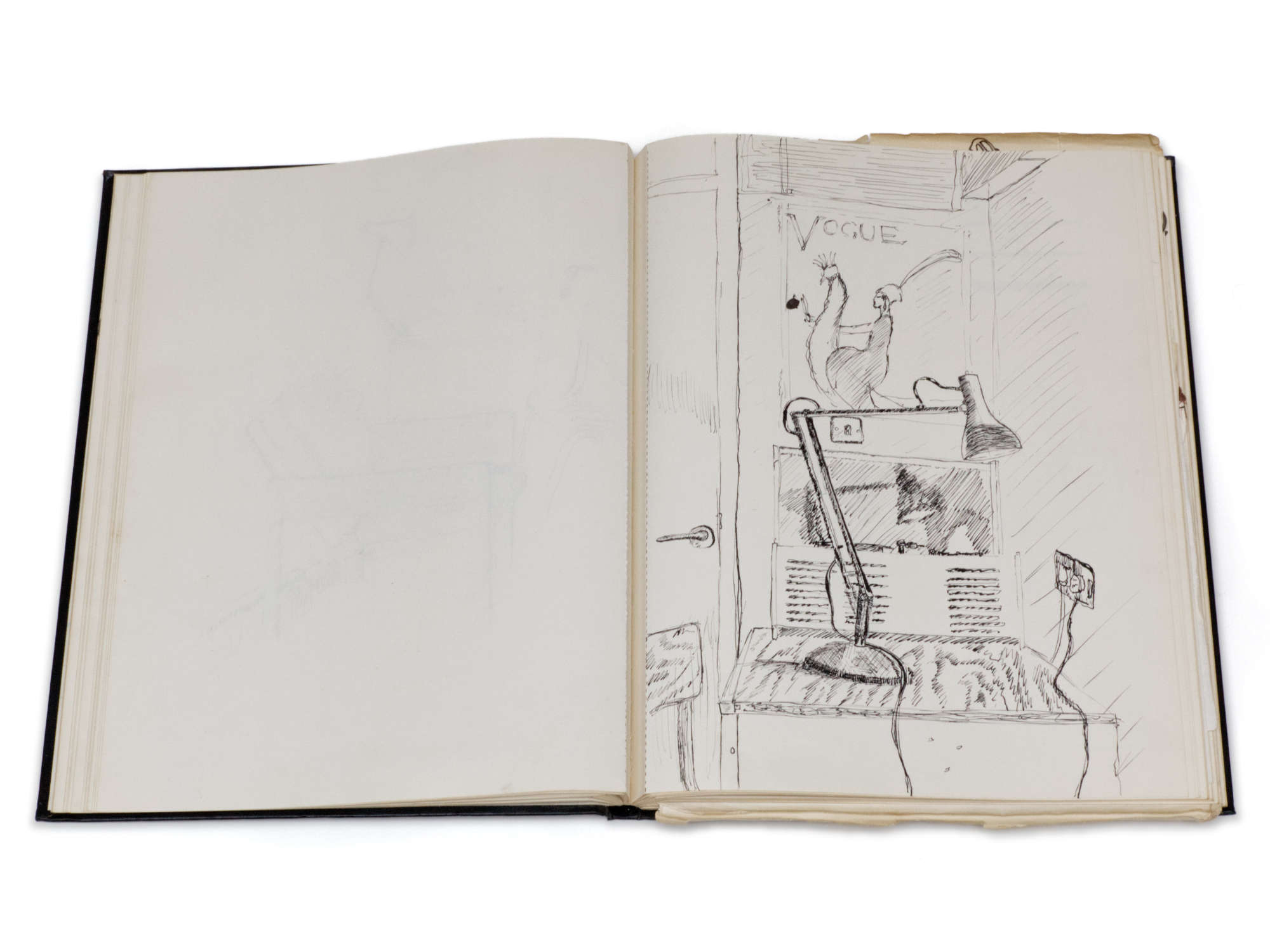

Sketchbook by the young Jasper Morrison with a drawing of his room at school showing his grandfather's Snow White's coffin.

© Jasper Morrison Ltd.

The radically reduced Plywood Chair by Morrison for Vitra, 1988.

© Jasper Morrison Ltd.

Unrealised concepts for a flat screen TV and HiFi for Sony, designed by Morrison together with John Tree, 1998

© Jasper Morrison Ltd.

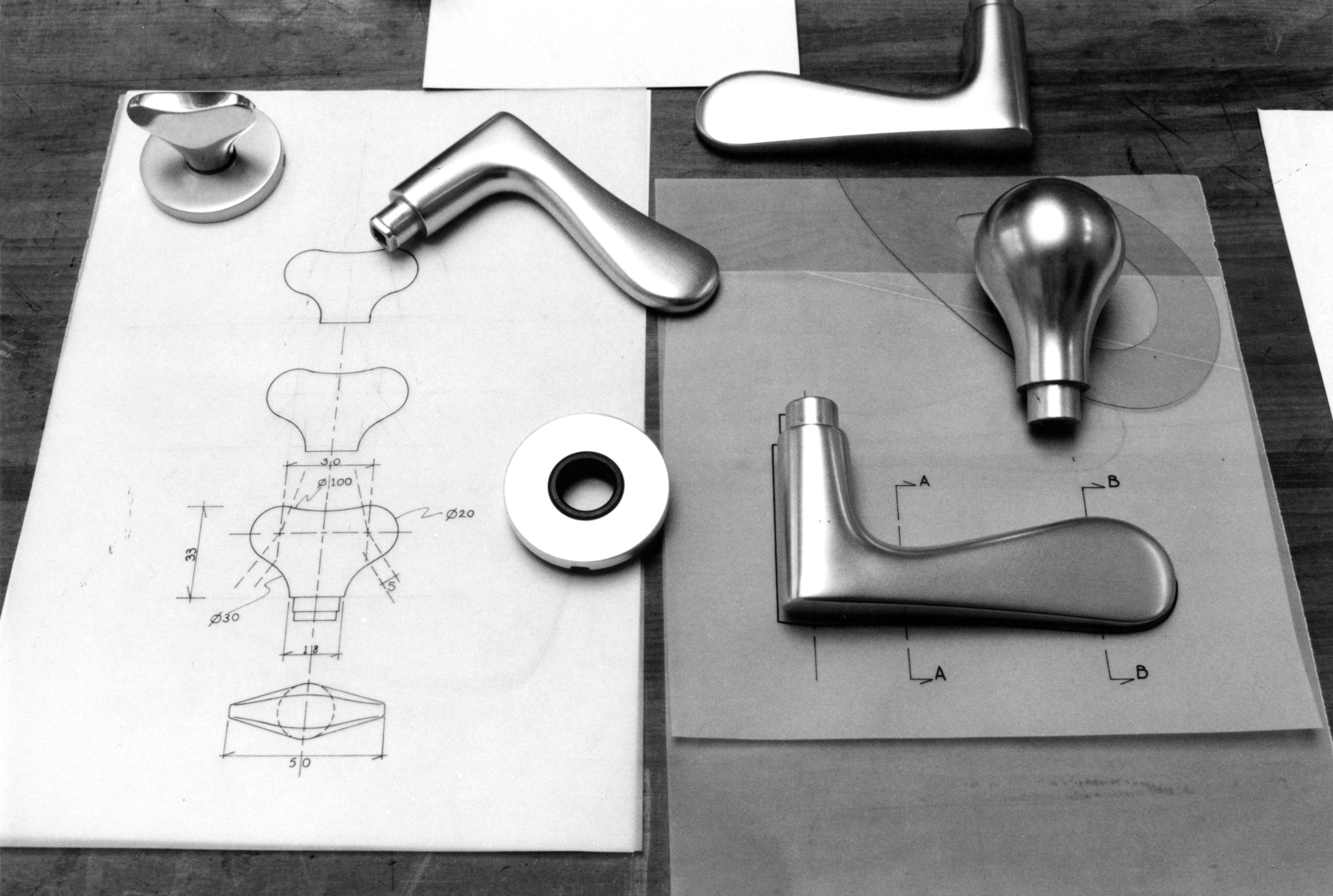

Door handle Series 1144 for FSB, Jasper Morrison's first industrial-produced designs, 1990

photo: Timm Rautert / © FSB

GT: Do you mean the 1960s and 1970s? My impression is that his vision reaches much further. He to this day is very much committed to the future of design and design education.

Exhibition "Super Normal", Axis Gallery, Tokyo, 2006, curated by Morrison together with Naoto Fukasawa

© Jasper Morrison Studio / Axis Gallery

APC (All Plastic Chair) design by Jasper Morrison for Vitra, 2016

© Vitra

Watch design by Jasper Morrison for the Swiss company Rado, 2009

© photo: Xavier Perrenoud/XJC, 2024

More Contributions

Jonathan Ive

Numerous international designers have expressed how much Dieter Rams‘ work means to them. But the impact of what Jonathan Ive did through words and actions for the Braun design revival of the Rams era was and is immense and ensures a worldwide response — to this day. Time for an interview with the long-time Apple design chief.

Fabio De'Longhi

In 2012, the family-run De’Longhi Group took over the Braun Household division. In our interview, Fabio De’Longhi talks about how he sees Dieter Rams‘ legacy and what he expects from the future in terms of design, production methods and management strategies.