"Design has to be alive"

Interview with Fabio De'Longhi by Gerrit Terstiege

Italian entrepeneur Fabio De’Longhi speaks about the acquistion of Braun Houshold by his family’s company, how he sees the heritage of Dieter Rams and what he expects from the future in terms of design, production methods and management strategies.

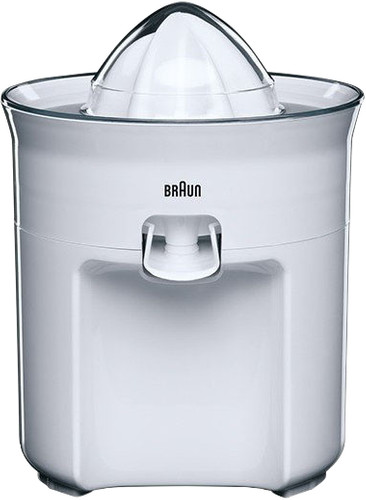

Left: Family entrepreneur Fabio De'Longhi, right: The Braun classic citromatic MPZ 2, 1972 designed by Jürgen Greubel and Dieter Rams, is now called the “Tribute Collection CJ 3050”.

© De'Longhi Group

The modern De'Longhi Group headquarter in Treviso was designed by Signorotto+Partners

© De'Longhi Group.

FD: Well, it’s not too complicated. You know, the design rules of Dieter Rams regarding simplicity, the wise use of materials, his concept of „as little design as possible“ for a honest, easy-to-use product – all that is a very important heritage. However, the world is changing: just think of the success of luxury goods in recent years for example. So today, we sometimes have to go a little bit beyond simplicity. It’s a fact that we have to stick to the heritage. But we have to take in to account what the consumer needs today. Also, the consumer interaction with products is changing as well: the way they cook, the way they iron. So in this respect, design has to be alive. Designers have to have a good understanding of the past, while looking into the future. And Phong has the ability to interpret the brand. Rules in design are fine, but they have to be interpreted.

FD: On one side I see the importance of respecting the regional design preferences. At the same time, I believe that consumers change, habits change, and brands must evolve. Otherwise you are kind of blocked and hostage of your original idea. So you have to move on and to be courageous and to understand what we have to keep from the past and what has to change. So in this perspective, the heritage of Dieter Rams is a very heavy one, because he was such a genius who created such beautiful products. But some of them are not contemporary anymore, because consumer expectations change. Technologies change—and habits as well. Just look at the many ways people drink their coffee today. In the past, most people were fine with drip coffee and now they want cappuccino. They used to have a big mug or a large carafe, and now they want a short cup or special milk. So protocols have to take these developments into consideration and also other things related to them. So you have to know where you are coming from, but you also have to be courageous to adapt. Otherwise brands die. Plenty great brands with beautiful designs have disappeared from the market. We forget that phenomenon sometimes, because the brands themselves are forgotten. So we have to make sure that we meet consumer needs. In the end, they should be happy with our products. It is a very important aspect to make products that people feel good about using. This must be kept in mind as a design goal all the time.

Front of the new automatic coffee maker Rivelia by De'Longhi

© De'Longhi Group

Model of the Kenwood series Chef: the British company Kenwood has been part of the De'Longhi Group since 2001

© De'Longhi Group

Kitchen machine with digital display: a manufacturer like Kenwood has to react to cooking trends

© De'Longhi Group

FD: Oh, yes, of course. We just have completed the acquisition of La Marzocco, a Florentine company, almost 100 years old, producing professional, high-end espresso machines. They just launched a cooperation with Rimowa, the German luggage company. A pop-up Café was created during this year´s Milan furniture fair. And there, a hand-made, limited-edition of La Marzocco coffee machines was created, quoting the aluminum grooves that Rimowa suitcases are famous for. That was a very special German-Italian cooperation. So what do we do when we buy a company? Our first mission and concern is to protect the company culture and to make sure that what makes a difference is independent, and stays independent. But we’re not making super many acquisitions. In the last 24 years, we bought Kenwood, Braun and Nutribullet. So we have now four brands in household and two in professional.

Three product examples of the blender company Nutribullet that is also part of the De'Longhi Group

© De'Longhi Group

More Contributions

Jonathan Ive

Numerous international designers have expressed how much Dieter Rams‘ work means to them. But the impact of what Jonathan Ive did through words and actions for the Braun design revival of the Rams era was and is immense and ensures a worldwide response — to this day. Time for an interview with the long-time Apple design chief.

Jasper Morrison