“Braun doesn’t need to follow these fast trends”

Interview with Duy Phong Vu and Markus Orthey by Gerrit Terstiege

Hand mixers and many accessories: Braun MultiMix 1.

© Roman Knie

MO: Last year we launched fourteen new products and this year it will be eighteen. And in the last few years, we have rebuilt the entire iron range. In fact, we’ve streamlined and expanded all the product categories. I also feel that the way of working here is more direct: one has much closer contact with people because we are a smaller organisation. And as Phong rightly says, the work is much more product-related and decisions are made more quickly. One makes decisions about new products together with a panel of experts, so to speak. And one also takes on many other tasks because we are like a small family: everyone is involved, not just those working in design.

Team meeting of Braun Household in Neu-Isenburg: Markus Orthey (left) and Duy Phong Vu (centre) with colleagues.

© Niels Geisselbrecht

GT: Speaking of expert advice: is there something like a timetable for the design processes of the various product categories—with fixed meetings and fixed roles?

Markus Orthey (right) with his former professor, the designer Florian Seiffert—creator of the famous Braun KF 20 Coffee Maker.

© Politecnico di Milano, Smart Design, 2019

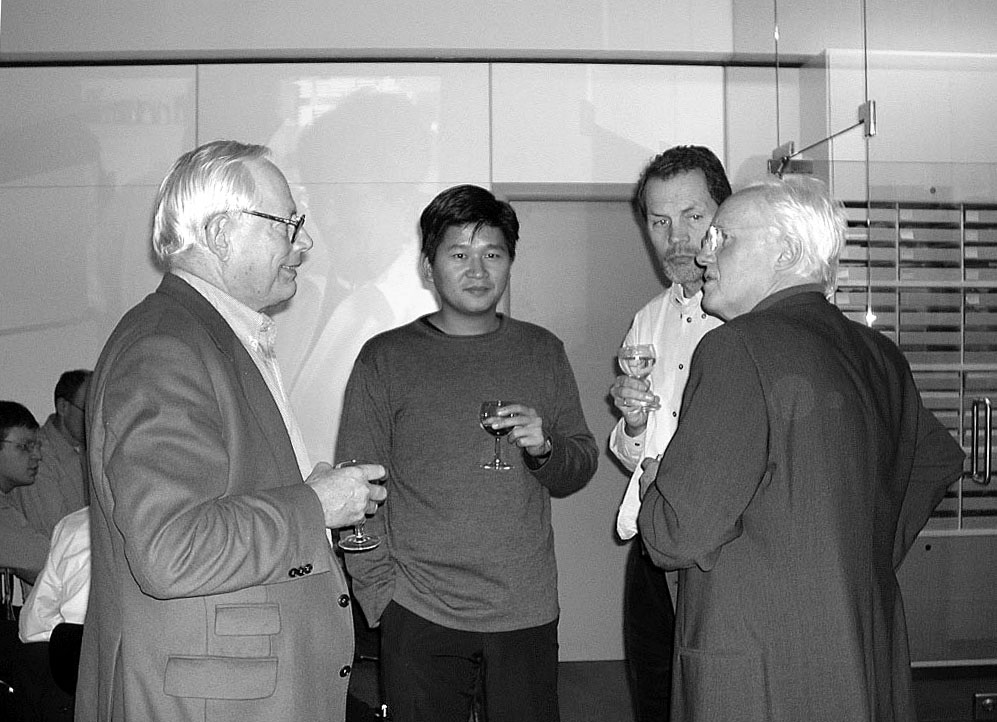

Dieter Rams (left), Duy Phong Vu (centre) and Ludwig Littmann as well as Jürgen Greubel, Braun Design department, Kronberg, ca. 2000.

© unknown

Left: Assembled and fitted step by step: The Vitsœ 606 Shelving System, in the flat of Duy Phong Vu. On the shelf: a Braun audio 2 system in anthracite.

© Duy Phong Vu

Right: Vitsœ spirit level and wall shelving.

© Duy Phong Vu

Markus Orthey’s atelier system in his living room. Designed by Peter Hartwein and Dieter Rams.

© Markus Orthey

Latest multi-function mixer MultiPractic 3, designed by Braun Household design team in Neu-Isenburg.

© De’Longhi Braun Household

DPV: We have set ourselves particular targets within the company, as the De’Longhi

Group. That applies to all brands. We started asking ourselves a few years ago where we could begin. We realised within our team that a concept involving bamboo cannot be considered sustainable at all, because bamboo needs too much groundwater to grow. And that’s when it really clicked for us and we started a co-operation with experts from Politecnico di Milano. They have one of the largest material laboratories in Europe and are helping us to go through the entire life cycle assessment of our hand blenders, coffee machines … In order to understand where we actually are. This has enabled us to set very clear targets, for example in terms of energy safety for our irons. Or water consumption for our fully automatic coffee machines. How can we improve this? How can we use recycled plastic sensibly? And as a design team, we have decided, for instance, that in future we will no longer design both hard and soft components for hand blenders. That’s because you have to separate different components in the recycling process.

MO: Besides the values of the Rams era, we now define sustainable design principles that we incorporate into our products. Phong has already stated as much: no more thermoplastic elastomers. We are now intentionally showing screws again to make it clear that the device can be opened and repaired. We tended to hide screws in the past. And we are trying to design products with significantly fewer parts. And using recycled materials. There has recently been a boom in PCR plastics. Two years ago, they were only available in dark brown or beige colours. All of a sudden, a year later, they were available in all colours, including pure white.

DPV: Yes, it’s certainly a process that will take years. But we are now in the implementation phase. We can no longer do without sustainability. This is one of the most important criteria that we are implementing in our design processes today: how to design components and housing parts.

CareStyle 9 steam iron station, designed by Braun Household design team in Neu-Isenburg.

© De’Longhi Braun Household

More Contributions

Jonathan Ive

Numerous international designers have expressed how much Dieter Rams‘ work means to them. But the impact of what Jonathan Ive did through words and actions for the Braun design revival of the Rams era was and is immense and ensures a worldwide response — to this day. Time for an interview with the long-time Apple design chief.

Fabio De'Longhi

In 2012, the family-run De’Longhi Group took over the Braun Household division. In our interview, Fabio De’Longhi talks about how he sees Dieter Rams‘ legacy and what he expects from the future in terms of design, production methods and management strategies.