Feedback on student designs: Dieter Rams at the familiar Vitsœ table accompanied by a Jieldé lamp in his room att he HFBK Hamburg

Foto: Jo Klatt © Hartmut Jatzke-Wigand

The Hamburg Years

Dieter Rams and Teaching

Gerrit Terstiege

A major chapter in the life of Dieter Rams about which little is known so far is that he was a professor of industrial design at the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg from 1981 to 1997. In search of traces.

Some scattered information, photos and quotes exist that relate to Dieter Rams’ Hamburg years. But there are not many. One example is the WDR film portrait Wer ist Mr. Braun? (1997), directed by Susanne Mayer-Hagmann. In it, scenes of the farewell ceremony of the long-time professor are shown, during which he gives his students a few important pieces of advice: ‘Try to be international. Don’t try to limit yourselves to our field, but go beyond that: you must know something about economics, about the general cultural trends. You must be philosophers, but also psychologists.’ Adrienne Göhler, the then president of the HFBK, sums up what the educational institution, which still has a strong artistic emphasis today, owes to the designer: ‘Dieter Rams had, of course, a decisive influence on product design at this university. He has, as someone who is a carpenter, architect, interior designer and designer, combined many disciplines. That is perhaps also the greatest legacy he left the school, which has been to bring the disciplines even more into dialogue and to network them. Since Dieter Rams is very radical, he declares: ‘Design without architecture and visual communication has no future at all. Full stop.“‘

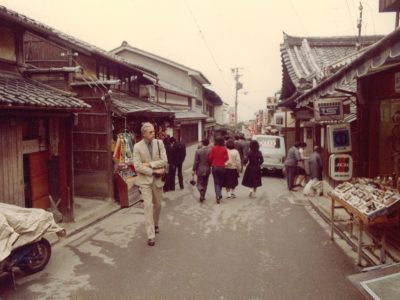

Yet, exactly how is it that he came to Hamburg? If one thinks about it, two aspects do not appear all that ideal: the pronounced focus of the HFBK as an art academy, in which product design plays a much lesser role, and the distance from Kronberg, which is almost 500 kilometres. A decisive, and evidently convincing, factor was the designer Peter Raacke (1928–2022), who was once a lecturer at the HfG Ulm. Like Rams, he was a native of Hesse and at that time already a professor at the HFBK. He championed the idea of attracting the renowned Braun designer to the university. This is how the designer Olaf Barski, who studied under both professors, remembers it. Rams was given three days off per month for teaching. This was, no doubt, a double burden. However, it was probably also good for him to occasionally take time out from the day-to-day business in Kronberg. And it was certainly inspiring for Rams to exchange ideas with young people about design matters, while also passing on his knowledge to the next generation. ‘During my time at the HFBK, he particularly appreciated the conversation, the one-on-one consultation, at his table,’ says former Rams student Peter Eckart, now a professor at the HfG Offenbach and founder of the Frankfurt studio unit-design. Preserved photos show the university workroom as it was furnished by Rams. One of his mottoes is: ‘One should do what is obvious’. This also explains why his furniture designs, such as the double-top work table mentioned by Eckart, his stacking programme, and his Vitsœ bed were also found in Hamburg. Rams also slept in this room, which saved him time and commute. It also saved the university a lot of money over the years on potential accommodation costs. On his desk stood an unpretentious black Jieldé lamp, which he knew all too well from Kronberg, Braun, and at home. Also within reach was the Braun HL1 desk fan and a Braun alarm clock. Rams had pinned drawings in DIN A-4 format on the otherwise bare walls, of which one showed a figure with its head in the clouds. These little playful scribbles, which can still be found in surprising places in his home today, show another, charmingly humorous side to him. In the film documentary mentioned previously, one briefly sees magazines lying on the low table, and the one on the very top is an issue of the Swiss architecture magazine Hochparterre, which shows him smoking, dressed in a trench coat on the cover. These Vitsœ pieces of furniture are now found in the Dieter Rams Room at the Hamburg Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, yet not as classic exhibits that are displayed behind glass. On the contrary, they were made available to be used by the changing scholarship holders. This is to the credit of the Braun collector, journalist and graphic designer Jo Klatt, to whom Rams left the furniture at the end of his time in Hamburg and who donated it to the museum. In the immediate vicinity of the Rams Room are parts of the famous SPIEGEL Kantine by Verner Panton. The contrast could not be greater.

On the occasion of the opening of the museum’s new design department in 2012, former students met with Rams, including Andreas Hackbarth: ‘As chance would have it, I was his very first student, right at the beginning of his teaching years in Hamburg. At that time, I had practically completed my studies and had added two more semesters, as a master student, so to speak. The long conversations in this initial phase brought us together in a special way. We are still in contact today.’ After his studies, Rams arranged for Hackbarth to work in the design department at Braun for a year. And when Rams was asked by Tecnolumen in the 1990s to design a work lamp for the company, he thought of his former student. Together, they perfected a design that Hackbarth had developed as a project for Rams in Hamburg. The lamp RHa 1 was not a commercial success for various reasons, including its steep selling price of around DM 1000. However, today it is highly valued among Rams collectors and remains a rare and shining example of close collaboration between professor and student that continued until the lamp was ready for series production. As Hackbarth states: ‘It was quite a real déjà vu moment for me in 2012 to see him sitting at his old desk again in the Hamburg museum. I brought him three green apples then, because they were always part of the standard arrangement on his desk when he was our professor.’

The Hamburg light designer Ulrike Brandi also studied with Rams in the 1980s and recalls: ‘He was reliable and you could ask him for advice at practically any time of the day or night, which was great. Rams rarely assigned tasks or themes, but simply supported one. Very meticulous and dedicated.’ In his book Weniger, aber besser /Less, but better, the designer presents selected student works that range from a stacking chair for the university auditorium (Angela Knoop) to an insulated bottle (Maja Gorges) to the concept for an ecological laundromat (Peter Eckart, Jochen Henkels). Rams is convinced when he states: ‘Good design begins with the education of good designers.’ But in his book, he characterises the quality of design education in Germany as ‘questionable’ and cites the large number of schools as the main reason. He argues that most do not have the capacity to train industrial designers ‘to meet the high and complex demands of practice’. Unfortunately, this situation has hardly changed in the last decades. A better education for fewer design students—this would indicate a new and very current facet of Rams’ famous credo.

More Contributions

Interview Hans Ulrich Obrist

Braun Design in Asia