The Bauhaus lamp by Wilhelm Wagenfeld

Gerrit Terstiege

There is no doubt that the Bauhaus lamp is not just any old example of durable design, but in fact counts among the world’s most famous ‘design classics’. This term, which is frequently and eagerly used in marketing, is for once truly appropriate here. Yet its enduring success and easily grasped technical construction tend to overshadow and obscure the design. With buzzwords like ‘Bauhaus’ and ‘Wagenfeld’, it would seem as though everything has already been said about it. And the lamp is still so commonplace in homes, upmarket furniture stores, and museums that this design achievement has virtually become a given. It is as though the lamp has always been around, as though its form were inevitable. This is probably the fate of many long-lasting products. Still popular today as a subscription bonus for newspapers and magazines (for an additional charge!), we encounter their frequently poor-quality copies in hardware stores, along with deceptive cheap replicas on dubious websites. For this reason, the manufacturer of the authorised re-edition, Tecnolumen in Bremen, felt compelled to publish a list of features that constitute the genuine product: https://tecnolumen.de/original/ Nonetheless, the Bauhaus lamp shares the misfortune of being plagiarised with many other classics, from the Eames Lounge Chair to Max Bill’s Junghans watches and Ray Ban’s Wayfarer sunglasses.

The "Wagenfeld-Lamp”, shown here is the model W 24 as it is produced by Tecnolumen. © Tecnolumen

Remarkably, not even Dieter Rams’ most famous and iconic designs, such as the T 1000 world receiver, the RT 20 radio or his wall system, have ever been subject to product piracy. It would be too complex and costly to do that — and the vintage technology and patina unique to the original products would be impossible or at best difficult to copy. However, as with the famous Braun SK 4, a dispute over authorship also surrounds the Bauhaus lamp. In his 1994 book Geschichte des Design in Deutschland (History of Design in Germany), Gert Selle writes: ‘It is precisely the convoluted design history of this Bauhaus lamp that demonstrates that the metal workshop was evidently not a hotbed of individual genius, but rather one of collective sensitivity to technical materials and new forms of expression. A type swiftly acquires a perfect form through ideas, experiments and preliminary designs that do not necessarily stem from a single source, in the same way that Thonet’s Chair No. 14 from 1859 cannot be clearly defined in terms of its origin.’

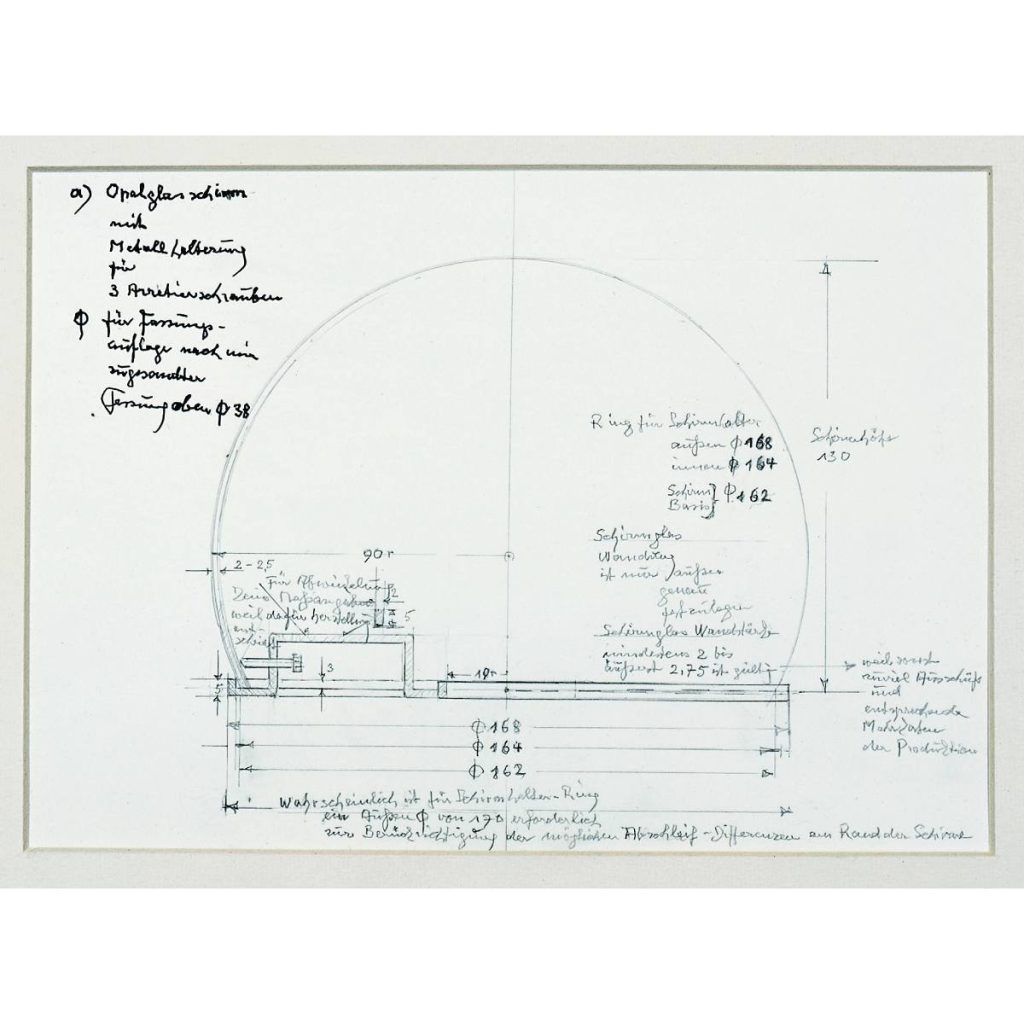

Construction drawing for attaching the lampshade by Wilhelm Wagenfeld.

© Tecnolumen

However, in 1999 a court ruling officially put an end to the discussions surrounding various individuals potentially involved in the design: “Copyright Act §§ 2, 3, 8, 23, 24 – ‘Bauhaus Glass Lamp’ – The author of the ‘Bauhaus Glass Lamp,’ characterized primarily by a round glass base, a glass stem containing a metal tube that conceals the electrical cord, and a white, almost hemispherical glass shade that hides the light source, is, in a legal sense, solely Wilhelm Wagenfeld. Hamburg Higher Regional Court, Judgment of March 4, 1999 – 3 U169/98.” Yet regardless of questions of authorship, it is certainly no coincidence that the luminaire, whether as WA 24, WG 24, WA 23 SW or WG 25 GL, continues to impress in all aspects of its design. Its longevity is inseparable from its simplicity, as the two characteristics are mutually dependent. The few materials employed were combined and coordinated so harmoniously in their proportions that the result is a symbolic yet clearly technical sculpture that pleases the eye even when switched off. Once switched on, it provides glare-free, subdued light that subtly illuminates its surroundings. And it has done so for over a hundred years.

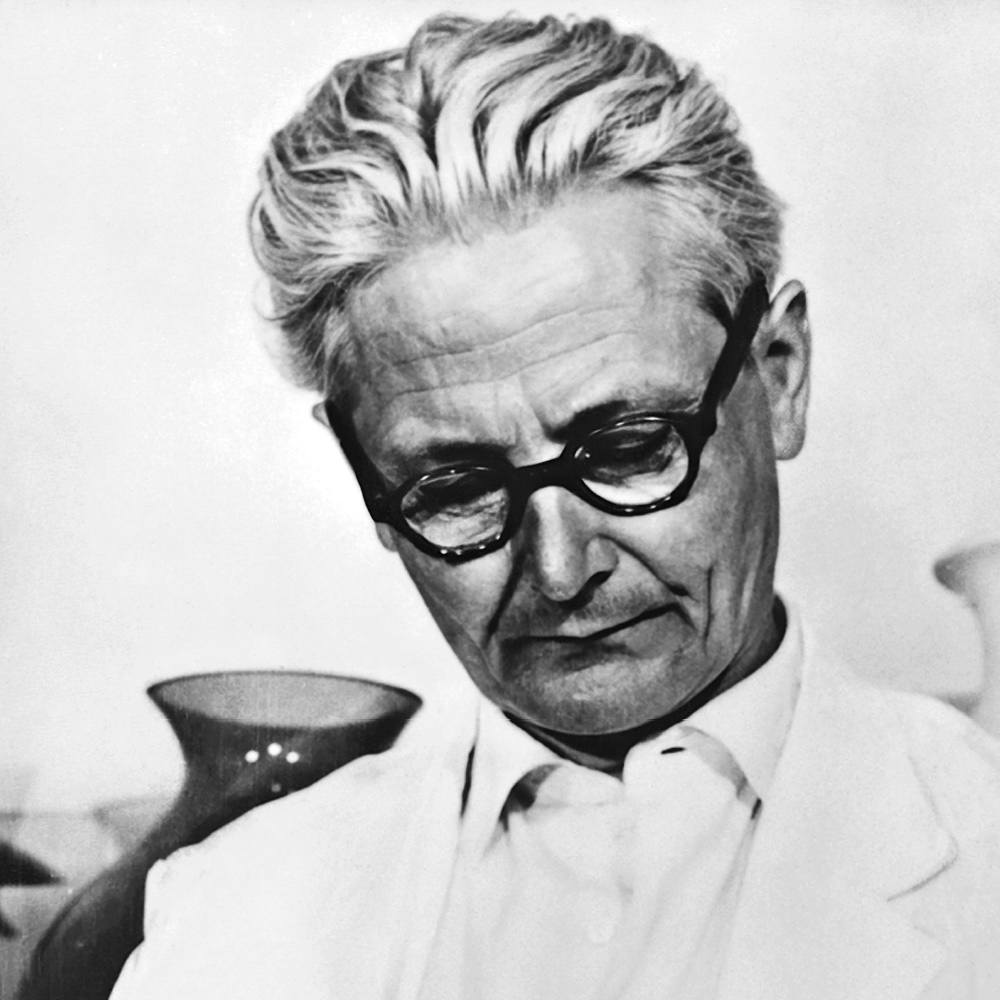

Portrait of the designer Wilhelm Wagenfeld (1900 - 1990) © Tecnolumen

More contributions

Durability: Design with a Long-Term Approach

In this series, we would like to present products that have stood the test of time on the market for decades. We wish to analyse which factors, materials and properties have contributed to an item being able to demonstrate exceptional durability in both functional and aesthetic terms — and not least in economic and ecological respects.

‘Runs and runs and runs…’, the Braun citromatic MPZ 2 from 1972

This small, unspectacular citrus juicer, made by the Braun brand, has been manufactured unchanged for over fifty years. There are many others available on the market, with different technologies on offer for separating the juice of oranges or other citrus fruits from the rest. Long-lasting technology meets long-lasting design. And that still applies to sales today.

A shining example of long-lasting design: the PH5

The design of luminaires undoubtedly offers a substantial level of freedom. From a technical perspective, the relatively straightforward task of directing light in a fairly focused manner does not require great complexity. However, it is precisely this creative freedom that has led to decades of designs featuring an abundance of extravagant, experimental, or unnecessarily dynamic luminaires.

/magazin/texte/bauhaus-leuchte/