“Rams challenged us!”

Interview with Jürgen Werner Braun by Gerrit Terstiege

Jürgen Werner Braun during his time as the managing director of Franz Schneider Brakel.

© FSB

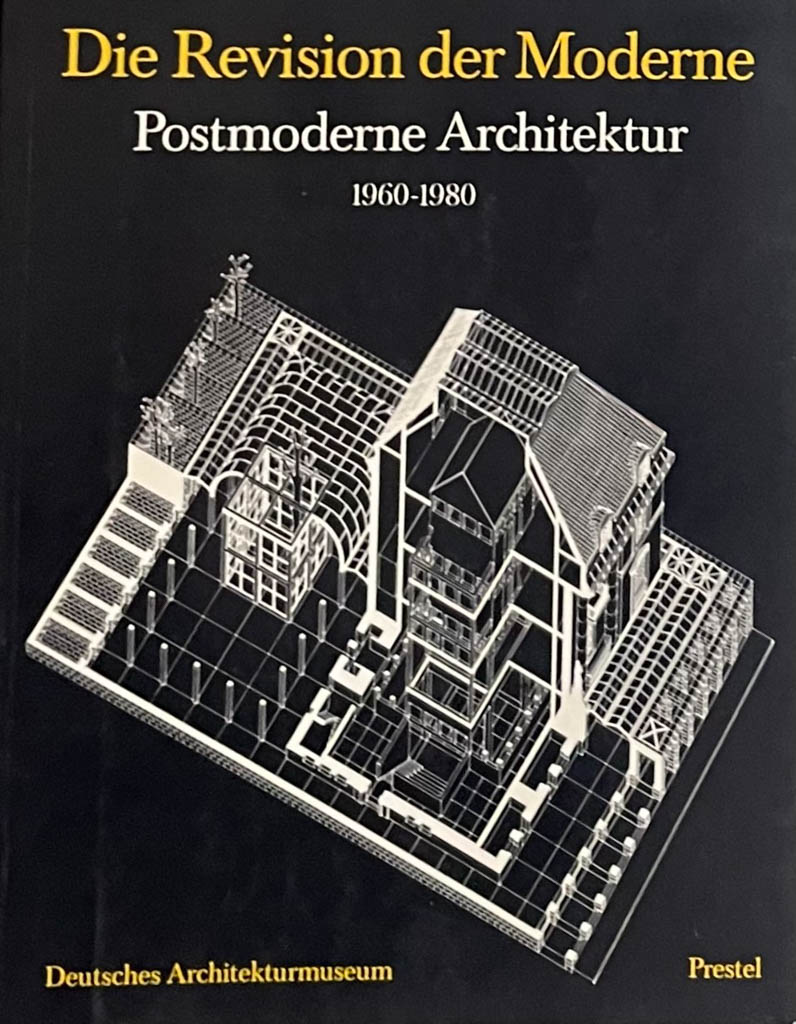

Left:

Exhibition catalogue Revision of the Modern, that provided Jürgen Werner Braun with important impulses, both in terms of content and design.

© Prestel

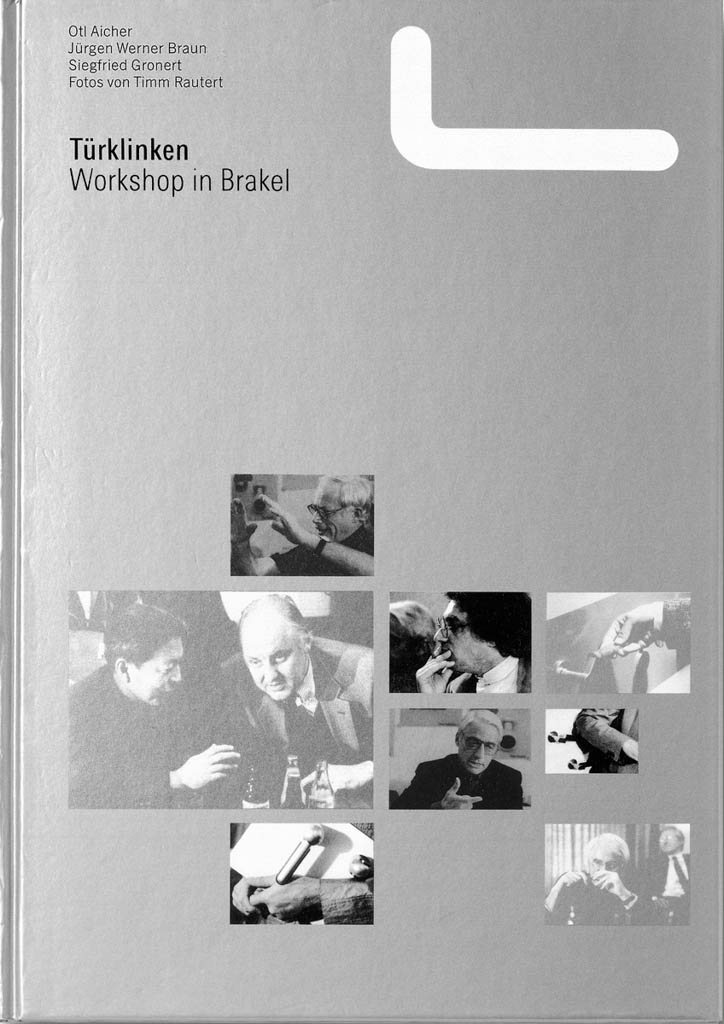

Right:

The book documenting the workshop in Brakel designed by Otl Aicher.

© FSB

GT: So, you realised that there was some catching up to do. Both for FSB as a company and for you as a trained lawyer without much architectural or aesthetic education. But your approach also demonstrates openness and curiosity.

JWB: I wasn’t quite that uninitiated. As a student, I was lucky enough to have a professor in Bonn who financed a semester abroad with a small research assignment. I went to Paris and enrolled at the university, at the law faculty. And at the weekends I visited the museums and enrolled at the École du Louvre. That was a wonderful experience that opened up many new perspectives and insights for me. And after reading the Frankfurt exhibition catalogue, I then selected twelve architects and designers and wrote to them asking whether they could imagine designing a new door handle. Surprisingly enough, they all replied.

The participants of the FSB workshop: Angela Knoop, Shoji Hayashi, Dieter Rams, Alessandro Mendini, Hans-Ullrich Bitsch, Mario Botta, Initiator Jürgen Werner Braun, Hans Hollein, Peter Eisenman, Petr Tucny.

© Timm Rautert

JWB: Yes, that’s true. Rolf Fehlbaum and I have always been on friendly terms. Together with Adi Dassler, we even had the honour of being counted among the three ‘escapees’ in the master’s thesis of a Dutch designer who could no longer stand it in Plato’s cave and simply left the world of shadows to stage and design their company and products (sports shoes, chairs, and door handles) afresh out in the world.

GT: Otl Aicher, your designer and design consultant, was not amused by Mendini’s invitation. Aicher and Rams are not known for pluralistic, stylistic experiments …

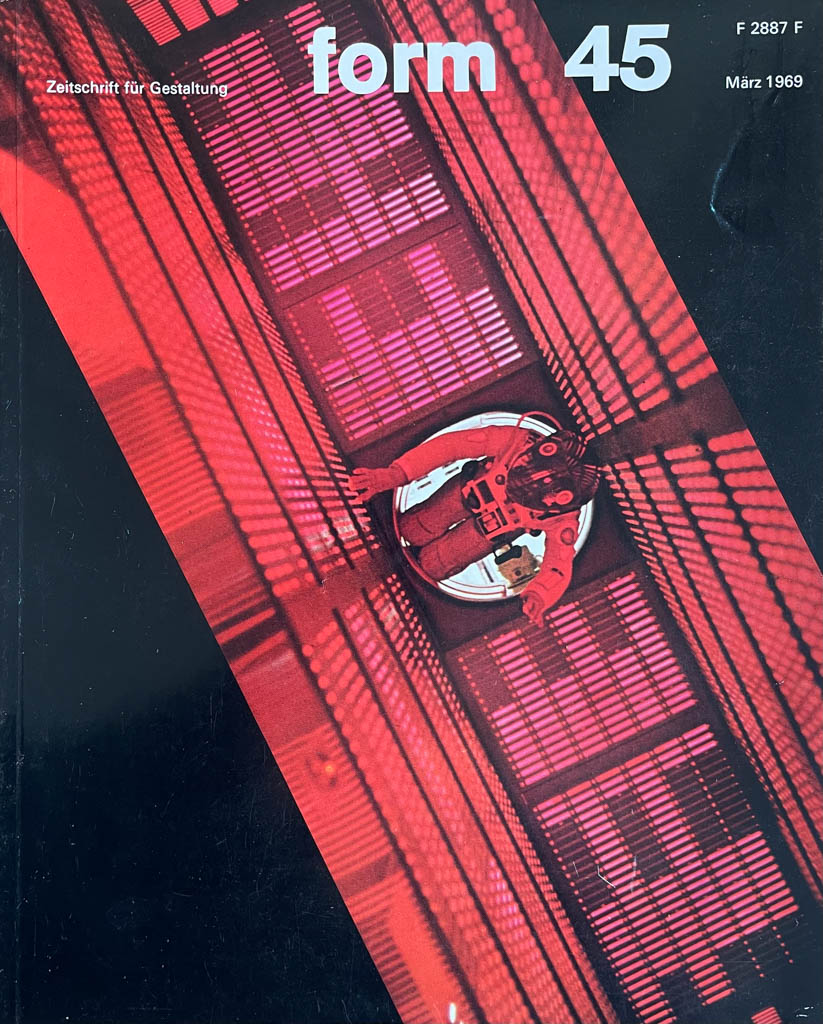

JWB: I would say no. The present day is just as exciting. One just has to walk through the world with open eyes. There are of course two sides to many things, like AI at the moment. In Stanley Kubrick’s famous film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, a human eventually survives a battle with the giant computer HAL, which in a way represents the first example of artificial intelligence. And for me, this survivor of the journey into space is the designer who is trying to survive in the world of artificial intelligence. That’s because there would be no innovation without people. What we are being led to believe today with artificial intelligence is nothing more than a large reservoir of human experience. It’s often just a case of old stuff being mixed up and rehashed—elements—and then people say: this is new!

Cover of the magazine form with a motif from the film 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick

© Verlag form

GT: The film was also well-received in the design scene in Germany—a film still from 2001: A Space Odyssey can be found on the cover of form magazine in 1969 … However, in order to understand that this film is still relevant today, in the field of design too, the young generation of designers would first have to be familiar with it. Which leads me to my next question: design history is hardly taught at many universities in Germany now. How do you see the importance of design history in the education of young designers?

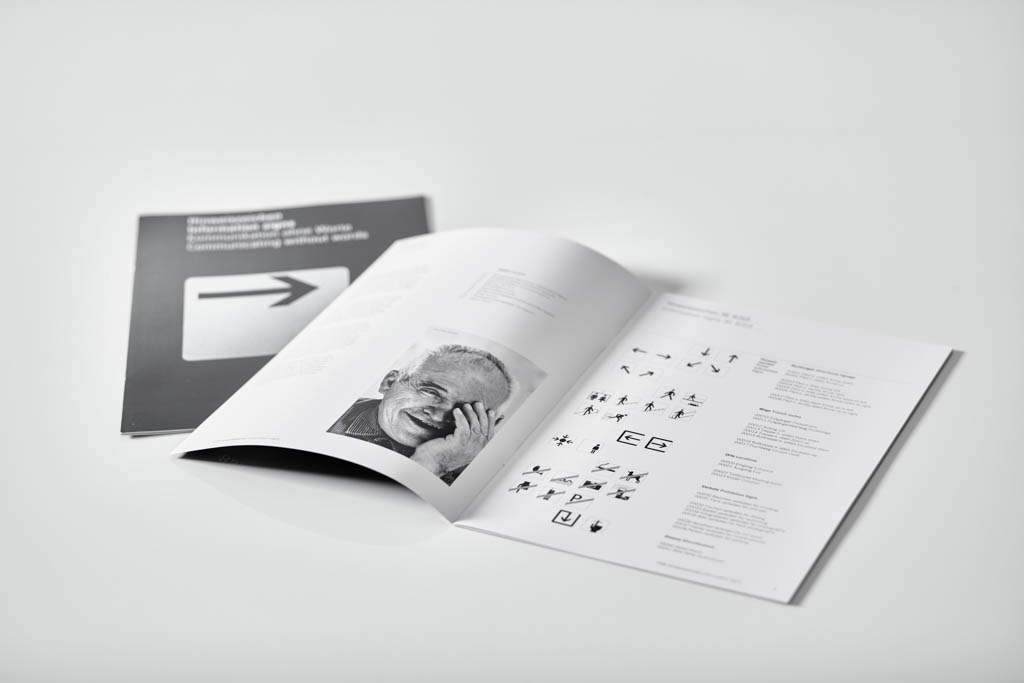

JWB: Yes, this is almost never or rarely taught anymore. Yet it would be very, very important. Design history can also be really exciting. I was reading Barbara Radice‘s catalogue on the flight back from New York, where I had seen a Memphis exhibition. And at some point, the stewardesses came to me and wanted to serve dinner. I had completely lost track of time and even refused the food because I hadn‘t finished the book yet! (laughs) As a designer, one should know what solutions were found in the past and why. But it’s quite complex. For example, the Ulm School didn’t just consist of Aicher and Gugelot. Many people worked there, often with very different stances. There were also disputes. And what the students then did with what they had learnt. Clivio, for example, with his unique hose connections, Neumeister with the trains, Zeischegg with his modular studies … what one can learn from this is also how diverse the history of design is and how design always adapts to the zeitgeist. There is no rigid, linear development like functionalism. There is no such thing.

Publication FSB Hinweiszeichen—Kommunikation ohne Worte, which was published on the occasion of the 100th birthday of Otl Aicher.

© FSB

GT: Dieter Rams has repeatedly emphasised that he doesn‘t like the word ‘functionalism’ at all. He generally avoids ‘isms’, rough categorisations, of which there are many in the history of design and art. If you look at his best designs, there really is a great sense of colour, of material combinations, and of proportions. His aesthetic sense is expressed here. It‘s not just about pure function.

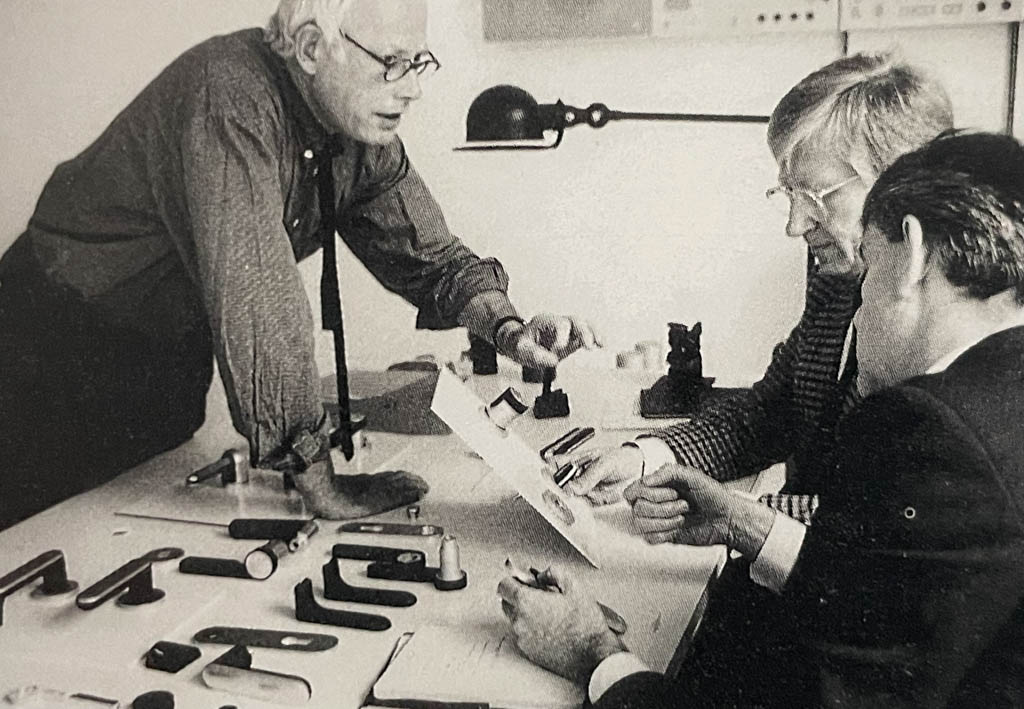

Meeting in Kronberg: Jürgen Werner Braun and FSB technical director Hans Barth discuss details of his designs with Dieter Rams. At the Vitsœ desk: the striking, black lamp from Jieldé.

© Timm Rautert

JWB: Well, when I was at his house for the first time, I noticed his desk lamp. And when he went into another room for a moment, I quickly looked to see what kind of lamp it was. It was a Jieldé, a French workshop lamp. The next time I was on holiday in France, I got myself a white one and a black one. Very solid, they don’t break. Very unpretentious. I think they’re great in their chunkiness and honesty. Then I naturally became interested in the designer Jean-Louis Domecq and the factory in Lyon.

GT: In a recent portrait shot of Jony Ive and Marc Newson, the two of them can be seen with black Jieldé lamps. I wonder how that came about! But the fact that a manufacturer like Jieldé nowadays focusses almost exclusively on one product, or on a small selection, is increasingly the exception. Many design companies are currently pursuing a strategy of the broadest possible product ranges. Stylistically, you can get anything from most manufacturers, from minimalist to playful. Doesn’t something like a stance get lost?

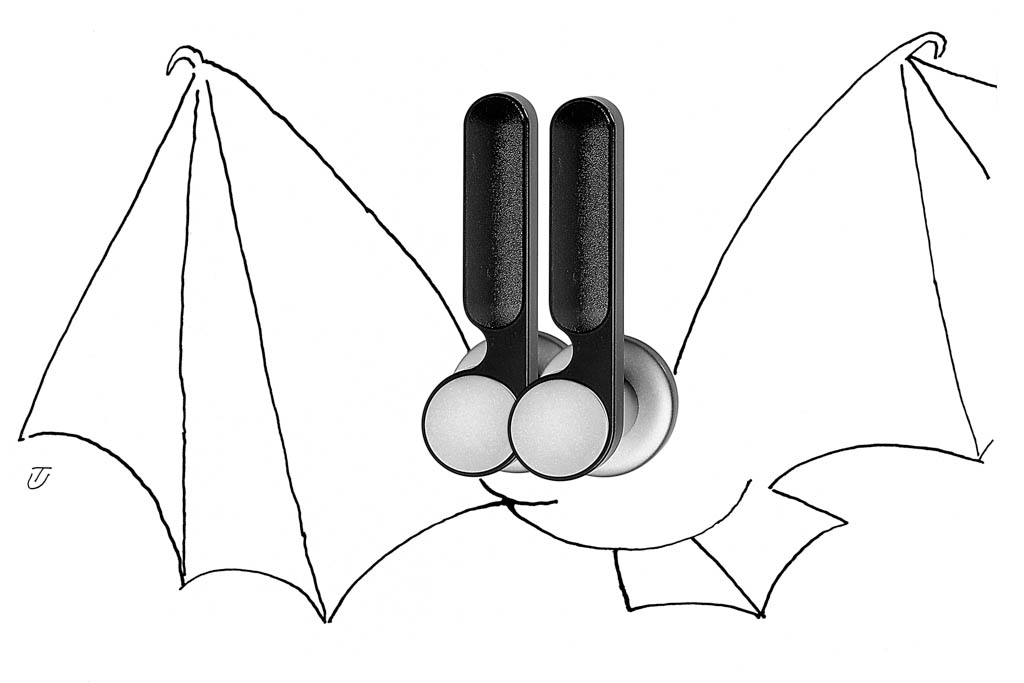

Jürgen Werner Braun convinced the French artist Tomi Ungerer (1931–2019) to create a visual series that FSB used in advertisements and postcards. Shown here is the drawing Fledermaus (bat) that includes Rams’ handles.

© FSB

GT: This brings us to the last question: what do you think is important in companies today and in the future? In terms of management, for instance, and in terms of creative and technical processes?

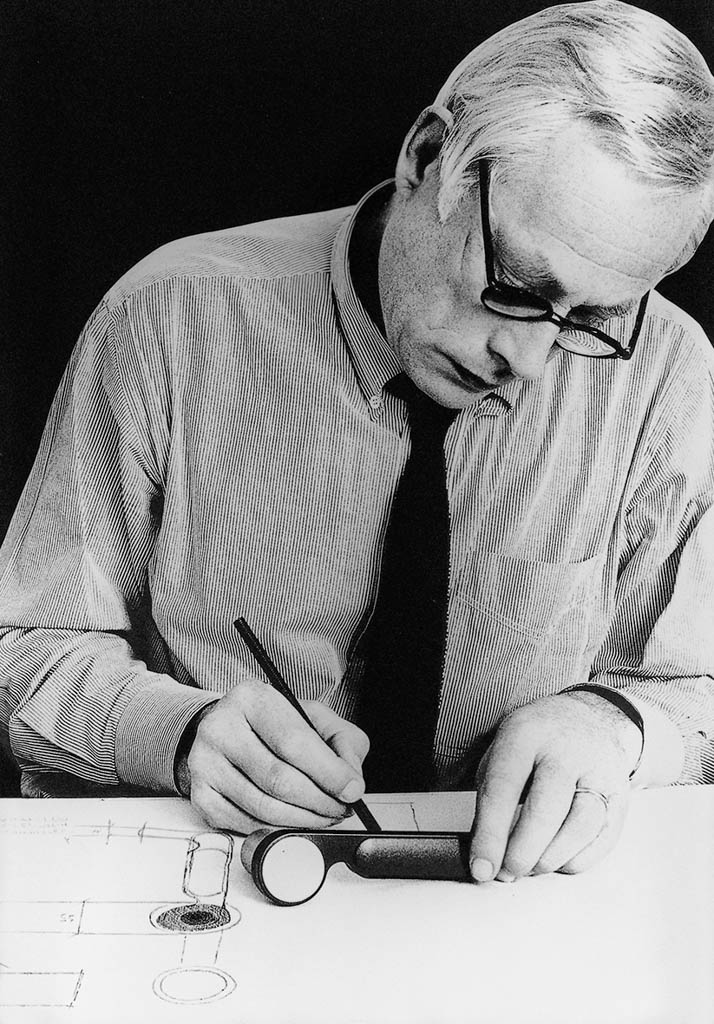

Left:

This portrait of Dieter Rams with his handle designs was often used by FSB, also as a large-format poster.

© Timm Rautert

Right:

product photos of the Rams handles.

© FSB

More Contributions

Jonathan Ive

Numerous international designers have expressed how much Dieter Rams‘ work means to them. But the impact of what Jonathan Ive did through words and actions for the Braun design revival of the Rams era was and is immense and ensures a worldwide response — to this day. Time for an interview with the long-time Apple design chief.

Fabio De'Longhi

In 2012, the family-run De’Longhi Group took over the Braun Household division. In our interview, Fabio De’Longhi talks about how he sees Dieter Rams‘ legacy and what he expects from the future in terms of design, production methods and management strategies.