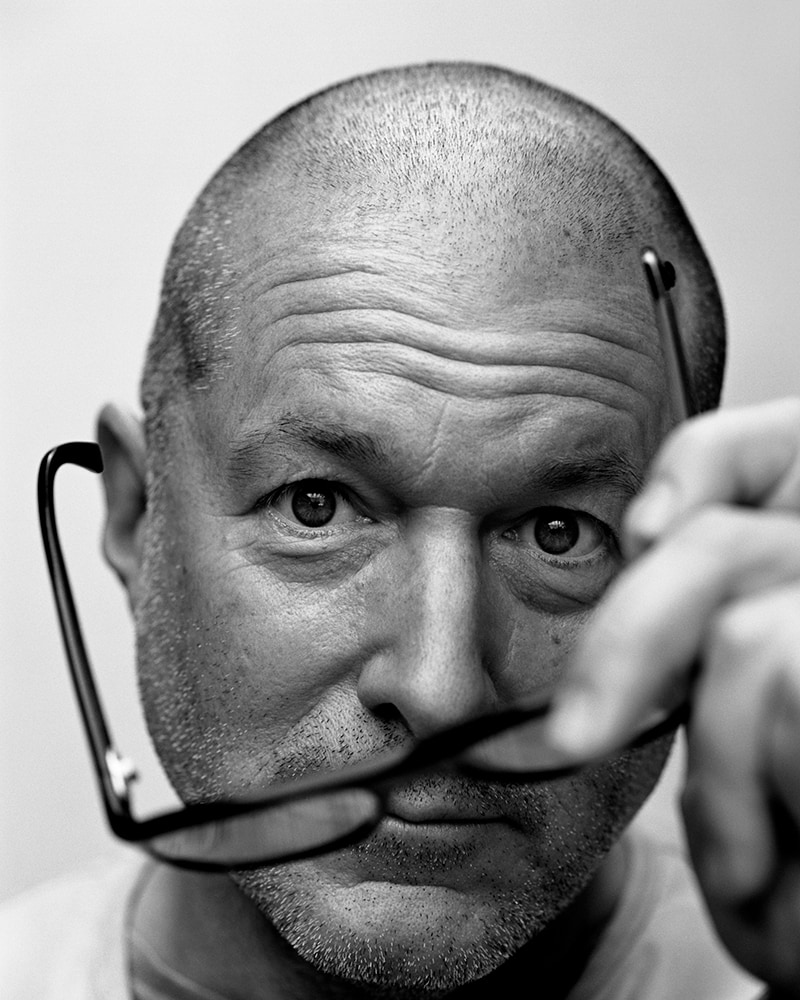

Portrait of long-time Apple design chief Jonathan Ive, taken in 2022 by British photographer and filmmaker Alasdair McLellan.

© Alasdair McLellan

“He articulated the way it should be”

Interview with Jonathan Ive by Gerrit Terstiege

Jonathan Ive, the long-time Chief Design Officer at Apple, is among the most prominent creatives who have been influenced by Dieter Rams and his design principles. Here, in one of his rare interviews in recent years, Ive speaks openly about his admiration—pointing out one important achievement of Rams that is often overlooked.

His parents' citromatic MPZ 2 was Ive's first contact with a Braun product. It was designed by Jürgen Greubel, Dieter Rams and Gabriel Lluelles in 1972.

© rams foundation

GT: In your foreword to Sophie Lovell’s book „Dieter Rams: As Little Design as Possible“, you write about the very first Braun product that entered your parents’ home: the citromatic MPZ 2. I recently acquired one because I wanted to understand what exactly triggered your admiration. I must say, it does have the appeal of a small sculpture

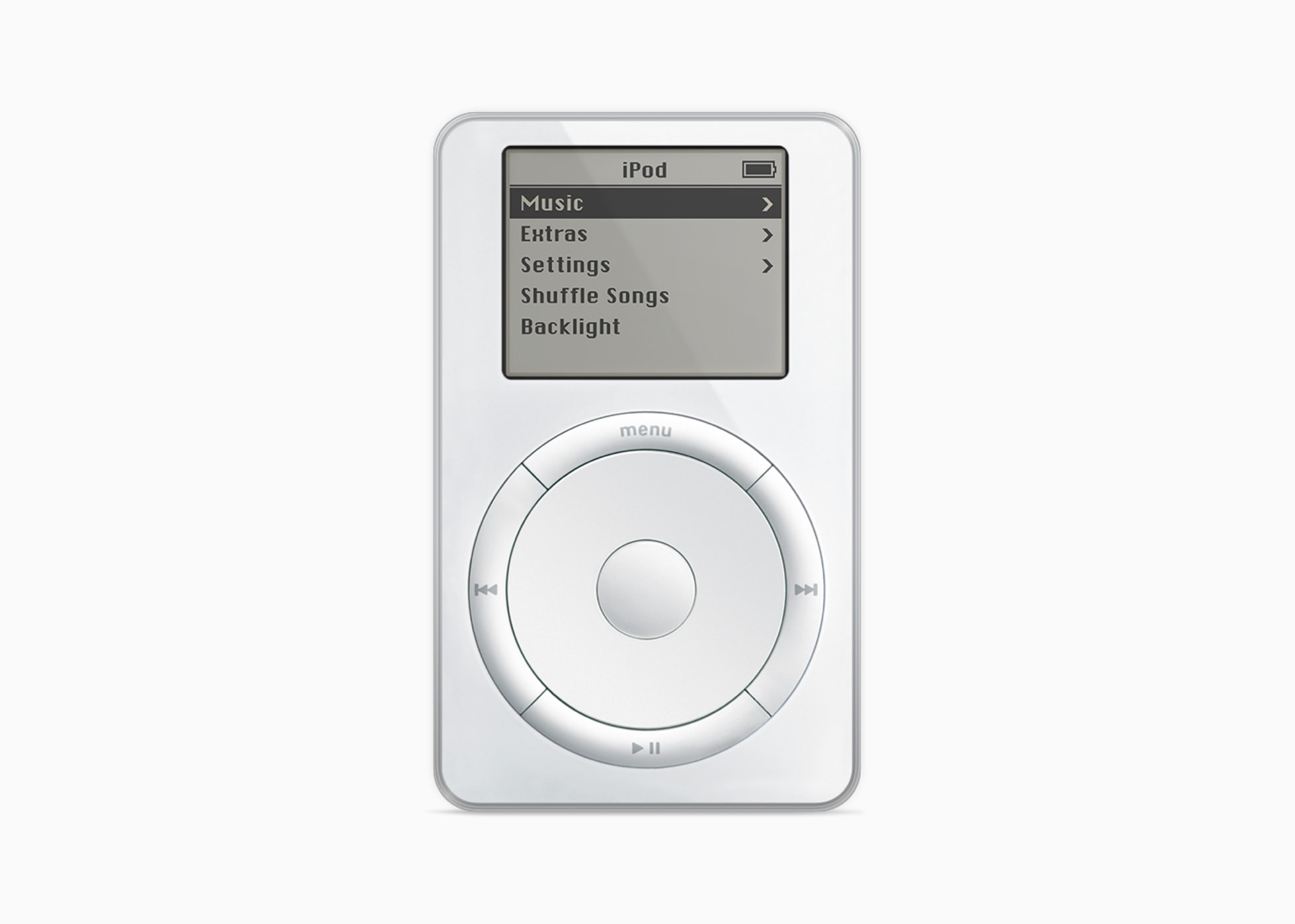

Apple's first iPod, designed by Jonathan Ive, attracted attention with bright white casing colour.

© Apple

Jony Ive sent Dieter Rams this iPhone—here Rams shows the calculator app: a digital homage to the Braun calculators designed by Dietrich Lubs and himself.

© Gerrit Terstiege, 2009

Clear design of Apple iMacs in different sizes. Design: Jony Ive.

© Apple

In 2023, Ive refined the Sondek LP12-50 turntable for the Scottish hi-fi company Linn.

© Linn

At the invitation of Jonathan Ive, Dieter Rams visited the Apple design team in Cupertino. On the far right: Vitsœ-CEO Mark Adams.

© Apple

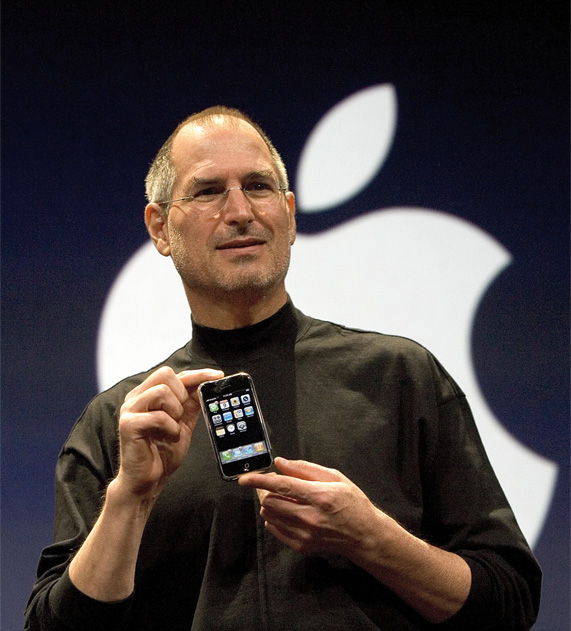

Apple co-founder Steve Jobs in 2007 presenting the first iPhone.

© Apple

More Contributions

Fabio De'Longhi

In 2012, the family-run De’Longhi Group took over the Braun Household division. In our interview, Fabio De’Longhi talks about how he sees Dieter Rams‘ legacy and what he expects from the future in terms of design, production methods and management strategies.

Jasper Morrison